Fair Play

TelstraClear aren’t always right, but they — and all of the other small telco’s that have been objecting lately — are right about this one. The Government’s plan to give the LFCs a 10 year regulatory holiday is a Bad Idea.

Classes of service and neutrality on the UFB

A couple of months ago (yes, I’m slow to post as always) I was made aware of a proposal that may mean the UFB networks favour certain types of applications and service providers over others, or favour legacy styles of service delivery such as walled gardens over the evolving trend towards over the top delivery.

What this issue boils down to is a guiding principal of neutrality. Now it’s hard to know what if any principals have been guiding the development of the UFB architecture since I cannot find any in the few documents that CFH and the TCF have so far made public. (This may be radical to suggest, but I think CFH needs to be more open and engaging. Hey CFH, how about doing a blog post on what you think about neutrality and take it from there?)

What should be the guiding principal here? Well we need to ask what we are building the UFB for and what we want it to achieve, and I can’t speak for other people, so this is only my perspective, but it’s one I think most people who consider the UFB as a project of strategic importance for New Zealand’s future will agree with.

The Government should not be taking on all the risk of building the UFB simply so that established providers can continue to provide the same services they do today, or entrench their positions. I believe the purpose of the UFB, and any similiar national broadband programme, is to provide a neutral platform that allows retail service providers (RSPs) to compete equally on the basis of how good their products are regardless of their size. For this reason the UFB must aim to minimize its influence on what shape those products take. Thus distinctions must not be made between types of applications or style of service delivery. That must be decided by the consumers and the competition between the RSPs.

So with that in mind I was concerned when I heard that the current proposal is have two classes of service, a high priority class and a low priority class, as illustrated in the table below taken from the TCF UFB Ethernet Access Service Description.

Let me be clear. This is stupid. (Or I’m stupid and not seeing how this is going to be used.)

What does this mean? Well it will depend on how it is going to be used. First let’s take a look at these two classes.

We have a high priority class which has tight SLAs. This class is not colour-aware, meaning that it doesn’t support the concept of bursting above the committed information rate (CIR). Excess traffic over the CIR is dropped. I do approve of the 5 ms frame delay (latency) and 1 ms frame delay variation (jitter) SLA. But I disagree with the 0.1% frame loss ratio. 0.1% is too much for what should be absolutely committed capacity through the network. Instead this frame loss ratio should be closer to 0.01%, but couched with availability, which is supported by the MEF framework that the TCF are sort-of using here. That is, we should say that 99% of the time frame loss will be below 0.01%, but 1% of the time there may be some failure or event on the network that causes it to go higher.

The other class has pathetic, almost non-existent SLAs. It is basically a service where if there is available network capacity at that time the packet will be forwarded, otherwise it may be queued for a full second, and may never get through. There is no defined FD or FDV, and the FLR at 2% is absolutely ridiculous as anyone who knows anything about networking will tell you. This document gives the impression that this class is colour-aware, but actually it’s still a single-rate class as the CIR is always zero.

I really don’t know how they arrived a this, I can imagine there was a lot of debate at the meetings, and I recognise that design by committee can be difficult at the best of times.

Ok-ok, so hurry and get to the point, you’re saying.

To me, the above implies that the two classes of service will be carried in separate queues through the UFB networks. The high priority class is the only class offering a CIR and will carry applications such as voice and video that require committed bandwidth. The low priority class offers no commitment and will carry Internet, possibly with an atrocious quality of service if the SLAs shown are any guide.

So imagine you’ve subscribed to a triple play package from your RSP. You have one phone, and one TV, so your RSP orders a service from the local fibre company with:

- 150 Kbps of high priority bandwidth for voice, enough for one voice call since you have only one phone.

- 10 Mbps of high priority bandwidth for video, enough for delivering one HD stream since you have only one TV.

- 50 Mbps of low priority bandwidth for Internet — an arbitrary number for this example, and presumably this will vary depending on each RSPs packages, e.g. there may be a 10 Mbps package, 50 Mbps package, and 100 Mbps package.

The UFB network receives traffic from many competing RSPs and delivers it to many subscribers over shared links, so queuing and scheduling must be used at these points within the UFB network to provide the desired differentiation between the two classes of service. The indication is that the high priority class will be given bandwidth before the low priority class in a strict priority or weighted fashion. (This is a simplification of the issue sufficient to illustrate the point below, but it should be noted that the problem is actually much larger, requiring the use of H-QoS to ensure fairness between the different RSPs and their respective subscribers.)

Now coming back to our scenario. Consider we are watching a VoD stream from our ISP during peak hour, and this is an HD stream requiring about 9 Mbps of bandwidth (depending on how much action is going on). As we outlined above this is delivered in the high priority class of which we have 10 Mbps to play with, so we can be certain the stream gets through in a timely manner without packet loss and the associated skipped frames or artifacts.

But we get bored of this, so turn to an over-the-top (OTT) video service (such as Hulu, NetFlix, or YouTube) for entertainment. These are delivered over our Internet service, which as we outlined above has 50 Mbps of low priority bandwidth with basically no SLAs.

Now we find that our OTT video service is getting a lot of buffering because it is peak time and there is congestion on the UFB network. It turns out everyone in our neighbourhood has come home after work and started watching TV. All of these TV streams are being carried in the high priority class so getting the share of the bandwidth on the UFB network before our Internet traffic. Our OTT service suffers as a result.

Hang on, you say, you’re no longer watching the VoD stream, but you are paying for 10 Mbps of high priority bandwidth to carry it. So when you’re not using that 10 Mbps for VoD where does it go? And who decided a VoD stream from your RSP is to be treated differently to a VoD stream from an OTT provider? You’re right to ask that. When you aren’t using your 10 Mbps of high priority bandwidth it gets shared out amongst everyone elses low priority traffic — it does not get assigned to you, you see only a fraction of it, even though you’re paying for it. And who decided that VoD from your RSP is more important than VoD from an OTT provider? Apparently CFH and the TCF did back in February.

So what’s the solution? Well this is a complex subject and there are a few solutions. In order to select the best solution the guiding principals must be established and the detailed requirements analysed. One could easily end up writing hundreds of pages on the subject, so given I get no reward for that, I’ll jump to those solutions that are readily apparent.

- The above two classes of service could be modified to make the low priority class dual-rate, supporting a CIR and EIR, and tightenting its SLAs, with the high priority class priced to discourage its use except for very low bandwidth and special applications. The UFB network will perform the necessary H-QoS to ensure fairness between the RSPs, i.e. between the aggregate of subscribers for each RSP, but not at a per subscriber level. The RSPs will be responsible for performing the H-QoS necessary to ensure fairness between each of their subscribers and appropriately prioritise their applications and if they choose to also OTT applications. (Some inventive RSPs will choose to give the consumer granular control over this through a portal.)

- As above, but the high priority class is simply dropped because it serves little useful purpose, and simplification is better.

- The UFB network performs per-subscriber H-QoS on behalf of the RSPs based on the purchased bandwidth profiles. Each subscriber is guaranteed the amount of bandwidth they actually pay for, but the H-QoS is configured with multiple queues in a mix of strict priority and weighted round robin fashions. The RSPs can then manage the markings of different applications to indicate the relative priority of them and which queues they should go into.

If anyone in charge is listening — please take another hard look at this. I am happy to eat my hat if I’m wrong, but this is an issue fundamental to the purpose of the UFB, and we want to get matters such as this correct up front, rather than trying to address it later on when there is no regulatory powers to do so (given the Government’s insistence on a 10 year regulatory holiday).

Whangarei case study (part 2)

I’ve been playing with PostGIS recently, so I thought I’d start part two with a quick map showing the dwelling density of each area unit from the 2006 Census and the roads from Whangarei District Council. The area units shown correspond reasonably closely to the deployment area indicated by the map in the Crown Fibre fact sheet.

Read more…

Whangarei case study (part 1)

Whangarei is the first town off the blocks in the ultra-fast broadband space race, with Crown Fibre selecting Northpower for negotiations back in September, then the ceremonious connection of a school a few days ago — a completely meaningless event as there is still no solid definition around the UFB that differentiates this from any other fibre connection in the country. But Whangarei is a nice place, so I thought I’d have some fun and look at it as a short case study.

Read more…

Are we getting the right deal?

Is New Zealand getting the right deal? Well there’s no question we’re doing a better job than Australia at the moment, but beyond that it is hard to know. The process is not transparent and the CFH has not released any of the standards that partners are expected to meet (if there are any). Worst of all, there is no set of national regulated services that LFCs must provide, and the Government has declared that the LFCs will be exempt from regulation.

Rather than expand again on the principals of such networks, I’ll do the reverse and list some of the things that I believe would be a failure of CFH to get us the right deal. I believe the following will result in less economic transformation, less social benefit, less competition, worse service, and — what everyone cares about — higher prices.

- Sporadically connecting homes on demand as opposed to connecting all homes in a structured manner as part of the roll out.

- Not requiring an open access network offering the basic wholesale layer 2 services.

- Not having a well defined set of wholesale layer 2 services and cost model for these.

- Not having a framework for how these wholesale layer 2 service will be enforced and enhanced over the following decades to meet the evolving requirements of service providers and their customers.

- Permitting cross subsidization of wholesale services.

- Not using a network architecture that recognises the importance of aggregation for manageability, throughput, and cost efficiency.

- Using home-run fibre.

- Running drops all the way from the cabinet as opposed to a NAP in the street.

- Using blown delivery from the cabinet (see above).

- Encumbering any LFC with any of the partner’s legacy investments. For example if Telecom were to propose the establishment of an LFC that took ownership of Telecom’s existing copper outside plant, existing cabinets, or existing equipment, this would be bad. These have next to no value once you’ve decided to build a new FTTH network. Doing this is only a way for the partner to try to architect extra return from these prior investments.

- Deploying outdoor ONTs as opposed to indoor ONTs.

- Installing battery backup for all ONTs. Only necessary for those requiring lifeline services for which mobiles are insufficient, and even then this is really a larger subject: should we even bother with a POTS service on the UFB networks?

- Permitting any LFC to operate non-access services in competition with service providers. LFCs must only offer services between recognised service providers and their clients, not between subscribers. This applies to both the layer 1 and 2 services.

- Having more than two POIs for the wholesale layer 2 services within any 30 km radius. (Roughly speaking that is. Varies with circumstances.)

- Encumbering the LFC with the requirement to provide housing for service provider equipment at non-POI sites. Roughly one cabinet in each 5 km radius is all that is needed to house the MSANs.

25,000 kms of fibre, really?

Work has taken me away (quite far away) from blogging for some time now. There are a few subjects I want to blog about, particularly regarding the architecture of the UFB network. If time permits I’ll try to get to these in the next few weeks. Also, I might consolidate this blog with my other blog, since my posting has become so sparse.

Meanwhile, a quick post on the proposal for Chorus to be the UFB partner. In this article it is claimed that Telecom has 25,000 kms of fibre already in the ground: Telecom hopes for a break on regulation if it separates.

Really? They’re not including Southern Cross are they? 🙂 That’s great, if it’s accurate. The problem is that probably more than half of this is running down state and local highways and linking towns and communities. It’s not the fibre in the street running past those homes in New Zealand’s urban areas that the UFB project is targeting.

To give you an idea of what is needed I’ll pick on Wellington, only because the council makes available the convenient fact that they maintain 654 kilometres of roads. This is good enough for us to make a first order assumption that the UFB project needs to deploy between 654 and 1,308 kilometres of cable and duct in Wellington to serve it’s 67,000 households. Why do I say 1,308 kilometres? Well sometimes we might need to run ducts down both sides of the street, in other cases there’ll be one duct down a street but lots of ducts drilled across the street to provide drops into homes. So simply doubling the route kms gives us a very nice fudge factor to cater to both situations.

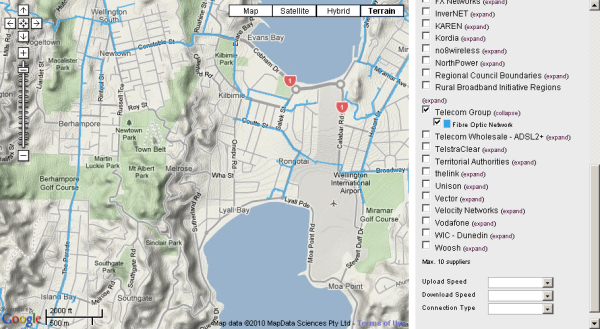

Now if we use the National Broadband Map to check out Telecom’s fibre assets in Wellington’s southern and eastern suburbs we see that the fibre is actually quite sparse.

What’s more, this fibre may not be appropriately designed for FTTH, requiring some reworking. The reality is that the value this brings is not as great as Telecom might like us to think. It may seem like I am beating up on Telecom here, I’m not. As I’ve said before, having Chorus as a partner does makes sense, if done right. I don’t have the confidence that the bureaucracy springing up around UFB could get it right though.

Roads vs. FTTH

This article (Supercity set task of coordinating broadband) reminded me of an old debate I had with someone on the funding for broadband.

Why is it that FTTH has had to face a far more stringent test of its business case than the billions of dollars poured into roads every year in this country? Even today there are deniers out there that still think the meagre $200 million per year over 8 years that will be spent on deploying FTTH is a waste. Yet anyone who looks at transport funding will know that road spending has almost no business case.

In this Auckland context, let’s take the proposed Waterview Connection, at $1.4 billion (though there are serious questions about that). You would expect that to spend $1.4 billion dollars would require a lot of analysis, first examining and setting the goals, and then looking at options on how best to achieve them. Well no, there have been absolutely zero comparitive studies according to NZTA. The decision has been made to build a road, and the only question has been what kind of form will that road take. So we can spend billions of dollars a year on roads this way, even while other countries are increasingly redirecting their transport spending away from roads. But when it comes to spending a comparitively meagre amount of money on something that all of the top countries in the OECD are doing (some have been doing it for quite some time now), and when it actually pays for itself, there are still so many naysayers. I would love to see a day when transport spending had to stand up to the same tests FTTH spending had in this country.

If there had to be a choice, between this one over-priced 4 km stretch of road with questionable returns, versus 75% of the country having FTTH, I think it’s pretty clear which is the better purchase.

Point-to-point vs. PON

Stephen Davies at Australian FTTH News has put up a recent presentation on the Point-to-point vs. PON debate. There’s some interesting debate in the comments too.

News Roundup

- Computerworld has a peice on Kordia’s submission. See Kordia warns of broadband risks (4 May 2009).

- According to Stuff, Vodafone is making a behind-the-scenes push to persuade the Government to establish a national consortium that would own telecommunications infrastructure. See Vodafone has ‘private plan’ (4 May 2009).

- REANNZ couldn’t find a suitable proposal from a potential supplier, so pulled the plug on its $15 million contribution towards a new submarine cable link. See Plug pulled on second Tasman cable (7 May 2009).

- Article at Stuff about financing the regional fibre companies, based largely on the submissions. See Debt a concern in fibre roll-out (8 May 2009).

- Some more on the failure to get a new Tasman cable underway. See Cable plan failure disappoints industry (10 May 2009).

- TUANZ blog post on Steven Joyce’s keynote at Telecommunications Day. See Joyce gives nod to fibre submissions (12 May 2009). The Minister is apparently saying LFCs will be allowed to wholesale layer 2 services now. But LFCs were already allowed to do this in the existing proposal. This is simply not enough, for residential users this must be mandatory.

The Australian Estimate

It is worth commenting briefly on one small matter brought up by this Computerworld article about Vodafone’s submission: Vodafone expresses doubts about shape of broadband plan.

“The actual quantum of investment required is not yet clear. Based on the estimates of independent expert Dr Murray Milner, the real cost of the investment may be as high as $5 to $6 billion,” it says. “In Australia, the government has announced a total requirement of A$43 billion to reach 90% of homes which when mapped to the New Zealand context indicates a figure closer to $9 billion. There is clearly more work to be done on the business case.”

$43 billion is certainly the upper limit. More realistic estimates, based on real-world experience in deploying FTTH, both in Australian brownfields and greenfields, put the likely cost at less than half of this figure. So simply scaling that figure to fit New Zealand isn’t advisable.